It is no small irony that one of the most dominant racing automobiles of all time was created because its engineering was not constrained by rules, only to be rendered noncompetitive and obsolete by a stroke of the pen. No matter the ending, the sheer perseverance, genius, and determination by one of the most legendary group of racers ever assembled will always be one of the greatest stories in racing.

In 1966 the Sports Car Club of America created a new race series, the Canadian-American Challenge Cup. Can–Am, as it quickly became known, was created as a series that would encourage development of very free-thinking engineering solutions to make cars go faster. It would become home to incredibly fast, unique cars that routinely broke lap records at tracks all around America. The series became perhaps the greatest form of motorsports competition that the world may ever see.

Initially, rules were held to an absolute minimum. A car had to have four wheels enclosed by bodywork, there had to be two seats, and there had to be requisite safety equipment. Everything else was up to the car builder. Teams could be as creative as they knew how to be, with no restrictions on chassis design, aerodynamic enhancements for the bodies, or restrictions on engine displacements and induction systems. People ran fairly conventional race cars with naturally aspirated V-8 engines but also ran over-the-top machines such as Jim Hall’s “sucker car”. It was the Wild West of racing series, and the spectators who came by the tens of thousands loved it!

They came to see the fastest cars of the day driven by the top drivers of the era. Generous purses and top level competition brought in many of the greatest drivers including John Surtees, Bruce McLaren, Phil Hill, Mark Donohue, Jim Hall, George Follmer, Peter Revson, Dan Gurney, Denny Hulme, Parnelli Jones, Jo Siffert, Mario Andretti and Pedro Rodriguez. It was an incredible show, but even with all this talent on display the fans began to grow bored with the yearly dominance of the McLaren cars with their big block Chevrolet power. So Porsche and Roger Penske decided to do something about it.

Roger Penske

Roger Penske grew up in Shaker Heights near Cleveland after his family moved there from New Jersey. Penske made money as a teenager by buying, fixing, and reselling cars. He played football, overcoming injuries to become a key player. Penske attended Lehigh University to study business, and while there became involved in racing his 1957 Corvette – sometimes skipping classes to compete. Penske’s father once said that the worst thing that could happen to him would be to win a race. “Then, the worst thing happened.” The racing hook was set.

Penske went on to become a top driver, but retired in 1966 to concentrate on his growing car dealership, on his transportation services businesses, and on managing his racing teams. His overall approach to the sport – as with everything else he did – was to demand thorough preparation, excellence in execution, and strict attention to detail in all aspects of the task at hand. That task could be anything – building a race car, organizing the team, analyzing the driving, or even operating the shop. He did not limit his thinking to conventional solutions, and this was to make him a world beater in racing. Team Penske is one of the most successful teams in the history of professional sports, with 16 owner victories in the Indianapolis 500, 458 major race wins, 522 pole positions, and 29 national championships.

Mark Donohue

Roger Penske once said in an interview “Mark was my best friend. What I realize now [ after Donohue was killed in a racing accident ] is that I wouldn’t have succeeded in my other businesses if Mark hadn’t completely taken over the race team.”

Mark Donohue, from affluent Summit, New Jersey, coincidentally bought a 1957 Corvette while studying engineering at Brown University and started racing. He won the first event he entered with the Corvette – a hill climb in New Hampshire. After graduation, he continued racing while working for his employer and raising a growing family. Donohue liked to drive fast and was always in trouble with the police. In order to avoid tickets and a license suspension, he and his girlfriend would swap seats so that some of the tickets and points would go to her and not to Mark! Eventually he got enough points to lose his driver’s license and would have to beg rides to get to work – at Penske!

Mark Donohue, from affluent Summit, New Jersey, coincidentally bought a 1957 Corvette while studying engineering at Brown University and started racing. He won the first event he entered with the Corvette – a hill climb in New Hampshire. After graduation, he continued racing while working for his employer and raising a growing family. Donohue liked to drive fast and was always in trouble with the police. In order to avoid tickets and a license suspension, he and his girlfriend would swap seats so that some of the tickets and points would go to her and not to Mark! Eventually he got enough points to lose his driver’s license and would have to beg rides to get to work – at Penske!

Donohue was successful at racing, and that success convinced Roger Penske to hire Donohue as a driver and team manager. They were kindred spirits. Donohue now had the ability to focus completely on the myriad of aspects involved in winning races. No detail was overlooked, and he followed a rigorous program of testing the engineering advances he was designing into the cars. He was another free thinker when it came to following the rule book. He put in long hours in development and preparation, working out problems and testing, testing, testing. It was grueling even to him, and he said of the effort “Believe me, this is only fun when you win.”

Donohue became the driver Penske could bank on. Even when he was severely injured, Donohue would show up at the shop or the track to supervise and help the team prepare for upcoming races. He was totally dedicated to the effort. When Porsche came calling, Donohue was more than ready.

George Follmer

George Follmer began racing a Volkswagen beetle in parking lot gymkhanas in southern California. He graduated to Porsches and won in several production classes at tracks throughout SoCal. As he made a name for himself, better rides came his way which lead to better finishes in better races which lead to even better rides coming his way. His big break came when he got a call from Roger Penske.

Penske asked if Follmer could drive his Camaro in a Trans-Am race for Mark Donohue who was having scheduling issues. Follmer did well, and when Donohue was severely injured in 1972 during testing Follmer was again asked to cover for him. This time, the car was one of the most advanced race cars ever built, the Porsche 917/10. It was unlike anything Follmer had ever driven. “The 917/10 was a brutal car because of its horsepower and braking capabilities, and it didn’t like high speed corners. It was good on slow corners, but the fast ones—and Road Atlanta has some fast ones—it was like you had to walk it through the corner on a leash before you unloaded it. And you better be pointing it straight when you did!” Follmer won the race by a full lap.

The following races weren’t as successful, and the car did not finish well. There were many problems with the car, and it took Follmer several races just to learn how to drive it at winning speeds. But learn he did, and as a result became the 1972 Can-Am champion! More importantly, he was able to give the Porsche engineers valuable insights on what was holding the car back. These shortcomings were addressed in the next car which was considered by many to be the ultimate Porsche, the Porsche 917/30. Everything was coming together for Team Penske.

The following races weren’t as successful, and the car did not finish well. There were many problems with the car, and it took Follmer several races just to learn how to drive it at winning speeds. But learn he did, and as a result became the 1972 Can-Am champion! More importantly, he was able to give the Porsche engineers valuable insights on what was holding the car back. These shortcomings were addressed in the next car which was considered by many to be the ultimate Porsche, the Porsche 917/30. Everything was coming together for Team Penske.

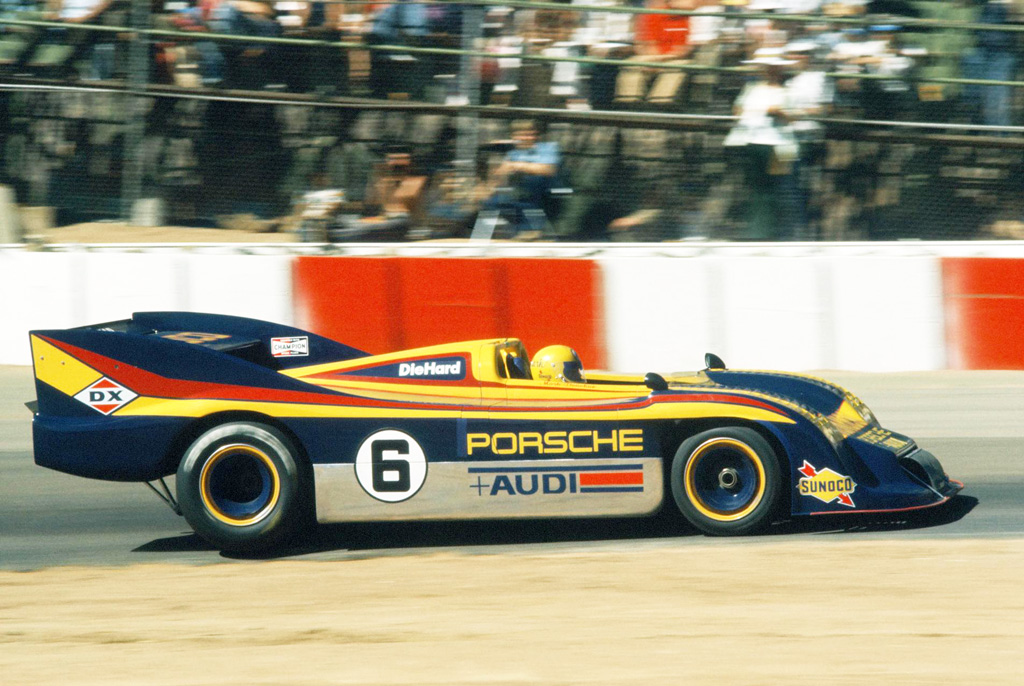

Enter the Porsche 917/30

After Mark Donohue recovered from his 1972 injuries, he was more focused than ever on perfecting his next Porsche. Nicknamed the “Panzer Porsche”, this machine addressed all of the shortcomings of the earlier car. The 917/10 was said to make 918 horsepower in the 1972 season, but the 917/30 turbocharged flat 12 typically ran at 1,100 horsepower but could make as much as 1,500 horsepower! The wheelbase was considerably lengthened which gave it consistent handling no matter how fast the section of track. The chassis was improved and the brakes were made stronger and more reliable. Even the aerodynamics of the body were tweaked, enhancing stability and downforce characteristics. It was an unbeatable Porsche, and with Donohue driving it won nearly every race in the 1973 Can-Am series. Donohue had his first Can-Am championship.

The Pen Was Mightier Than The Piston.

Donohue’s championship was deserved. An enormous amount of time, talent, effort, and money had gone into developing and fielding the ultimate Porsche. In fact, costs for the race series in general had become so high that only a few private race teams could campaign even the second-tier car, the previous year’s Porsche 917/10, which was now obsolete. Plus fans were starting to grumble about the series being so thoroughly dominated by Porsche that no one else had a chance to win. Something had to be done to make the other teams more competitive to bring excitement back to the series.

By 1973, America’s political climate was turning against fuel intensive motorsports, particularly with the OPEC oil embargo creating lines at the gas pumps for the very race fans that were attending and keeping the series profitable. So, with the stroke of a pen, the Can-Am rule makers limited the amount of fuel that could be consumed by the 917/30 during a race to 73 gallons for a 200 mile event. In order to make the fuel last 200 miles, the car would have to be driven at such a reduced speed that it would be sure to lose races. A victim of its own success, the Porsche had run out of gas.

Epilogue

The 917/30 was driven in one more Can-Am race in 1974, but it was the end for the car’s racing days. Mark Donohue did drive it one more time, taking it out of mothballs to set a closed-course record of 221.160 miles per hour at Talladega.

Less than one week later, Donohue was testing a Grand Prix car in Austria and had a tire deflate at speed. He tried to make the next corner, but lost control of the car, hit the catch fence, and went airborne. Debris from the shattered car injured one corner worker and killed another. Donohue appeared to be unhurt, but in fact his head had struck a signpost before the car came to rest. He checked into the hospital the next day complaining of a terrible headache. Soon after he fell into a coma and died before anything could be done for him. He was 38 years old.

George Follmer continued to race, and was considered one of the top drivers of that time. He was the longest-running substitute driver that Penske ever had. He considers the 1972 Can-Am race at Mid Ohio in the Porsche 917/10 to be a race for which he wants to be remembered. He won the pole, the race, and held the qualifying record. He had finally tamed the monster he was driving.

Roger Penske is probably the most recognized name in American motorsports, a recognition that is respected the world over. Roger Penske changed the way races and race teams were run, taking a sometimes haphazard sport and making it thoroughly professional. He lead this transformation by example. When Penske and Donohue arrived at Gasoline Alley for the first time in 1969, they were met with mockery and derision. No one had seen anything like this in racing before. Everyone on the team came in every day dressed in clean and pressed Sunoco branded team shirts and spent considerable effort keeping the car, surroundings, and even the garage floor clean. The driver communicated with the team using engineering terms to discuss the handling characteristics of the car. The whole effort displayed precision and determination. A new day in racing had begun, and it paid off in Penske’s first Indianapolis victory in 1972. The driver was Mark Donohue.

A lucky kid, circa 1973.

William Hoffer